AlarisPro Wants to Bring Drone Fleet Management to Another Level by Following the Lead of Manned Aviation

by Danielle Gagne

Being able to demonstrate to regulatory bodies drone safety and reliability is something that should be top priority for the commercial drone industry if we want to obtain advanced operations that can enable the industry to mature and grow. But how we determine safety and reliability as an industry is not always in line with how regulators view and define safety, which is very much defined by decades of experience with manned aviation. Figuring out how we can go about bridging that gap as easily and transparently as possible can make all the difference for the industry maturing.

This is why companies like AlarisPro have developed user-friendly, manned aviation-grade, fleet management software for the unmanned aircraft industry. They want to provide unmanned aircraft with processes similar to how manned aviation conducts in-depth, component-level flight checks, but with speed and ease of use in mind. To ensure the information is accurate and timely, they have established themselves as intermediaries between manufacturers and operators, gathering a repository of up-to-date information about components that go into a drone from both groups of stakeholders.

Commercial UAV News spoke with Anthony Pucciarella, President of AlarisPro, to talk about how it first got started, the unique capabilities of their fleet management software, the challenges of fleet management, aviation safety, and much more.

DANIELLE GAGNE:

How did AlarisPro first get started?

ANTHONY PUCCIARELLA:

Around 2014, I started a company called Alaris. And it was a consulting company where we were trying to infuse the aviation culture that I had from my manned aviation background into the unmanned industry. At the time, it had nothing to do with fleet management. It was really about building manuals and processes for manufacturers and operators. We were doing waivers back then including COAs (Certificates of Waiver or Authorization), and then it migrated into 333 exemptions, and Part 107 waivers. So, we created that company and very quickly we started doing services as well. We created program documentation, procedures, and training to illustrate how an organization could have a solid unmanned aviation program.

We then started getting into public safety and training public safety organizations because they were the ones that needed professional programs first. Some of the smaller companies could get away with not having professional programs. But a public safety organization, like a fire department or law enforcement agency was subject to more scrutiny and had to do it right. Very quickly after getting heavy into providing services and training, we realized there was no effective tool for fleet management at the time. There were products out there at the time, but they were all basically spreadsheets with an attractive map and user interface.

I learned early from my background as an aeronautical engineer, airworthiness engineer, and an operational test pilot for the Navy to consider an aircraft as a system of systems. Whereas an aircraft is a flying system but within that system you have subsystems such as electrical systems, fuel systems, hydraulic systems, and so on. And how each one of these subsystems performs contributes to the overall safety of the overall system, the aircraft. So, how all those things fit together is what we call the systems of systems or the systems engineering approach.

In the Navy (and in aviation in general), we assess these subsystems and how they impact airworthiness. You can’t just look at how often you’ve flown the aircraft, you have to look at the components such as the propellers and all the things that create single point failures. Consider a quadcopter, for example, which I call a flying bundle of single point failures. If you trace the propulsion system, where it goes from a battery, to a power distribution board to an electronic speed controller out to a motor then a prop, and if any one of those items fails in a quadcopter, the aircraft literally falls from the sky. In manned aviation, we always strive for graceful degradation as a system of systems degrades. In unmanned aviation, there’s a lot of “not very graceful” degradation.

Our point is that you can’t just look at the aircraft, you have to look at these single point failures and how they contribute to the overall reliability of the unmanned aircraft. So, what we said was these single point failures are important and we need to understand what their expected life is, what is the mean time between replacement, what we call MTBRs, and what’s their mean time between failure—MTBF. These are all manned aviation standards that have been borne out through decades of lessons learned and engineering analysis. Because unmanned aviation is part of aviation, it’s very important that we look at these safety metrics, but few organizations are looking at them from that perspective. And that’s what we did. We created a software system based on the premise that, “we’re not just worried about entering flight time and being able to say the aircraft has a certain number of hours on it. But we want to know how many hours does the motor have on it? When was the last time the motor was changed? When’s the last time the motor was inspected? How many hours should we get out of these propellers?”

We then compile that data into our fleet management system and look not only at one specific aircraft or a model of aircraft, but all the components of many different aircraft. What we found very quickly was that a lot of the same components were on lots of different aircraft. So, we look at them across multiple models, and then provide an analysis of how it does across the board on everything, and then we assess what that looks like on that specific aircraft.

So, this is a long answer to say that there was a huge void that we were able to fill, and we’ve been filling it since 2016.

What challenges present themselves when we scale up from flying one drone to multiple drones?

The requirement is that whether it’s one or a hundred, they all have to be reliable. And if you take a look at the data requirements for one aircraft, whether it be medium size, small, or large UAS, as you scale those out to larger fleets, whether it is a fleet of 50 aircraft or a swarm of 50 aircraft, the data requirements, and the need for software to manage those data requirements, grows exponentially. As you look at aircraft, and as the number of those increase, the corresponding increase in data and the necessity to have software to manage that data is crucial. We always say that it’s not just the aircraft that you have to worry about, it is what you are carrying as well. For example, if you were flying a transplant organ, medical test samples, or something else that was life critical, of course we want the aircraft to be reliable, but we want the aircraft to be reliable also because we want our payload to get where it needs to go. Making the aircraft reliable is not just so it doesn’t present a danger by falling out the sky but that it also gets the payload or sensor where it needs to go. AlarisPro is collecting and analyzing the data to show that you as a manufacturer, or you, as an operator can say with confidence that this is what my system is going to do, this is what I’m intending it to do, and this is how well it is doing that.

What are some ways that fleet management software, like AlarisPro, can help with those challenges?

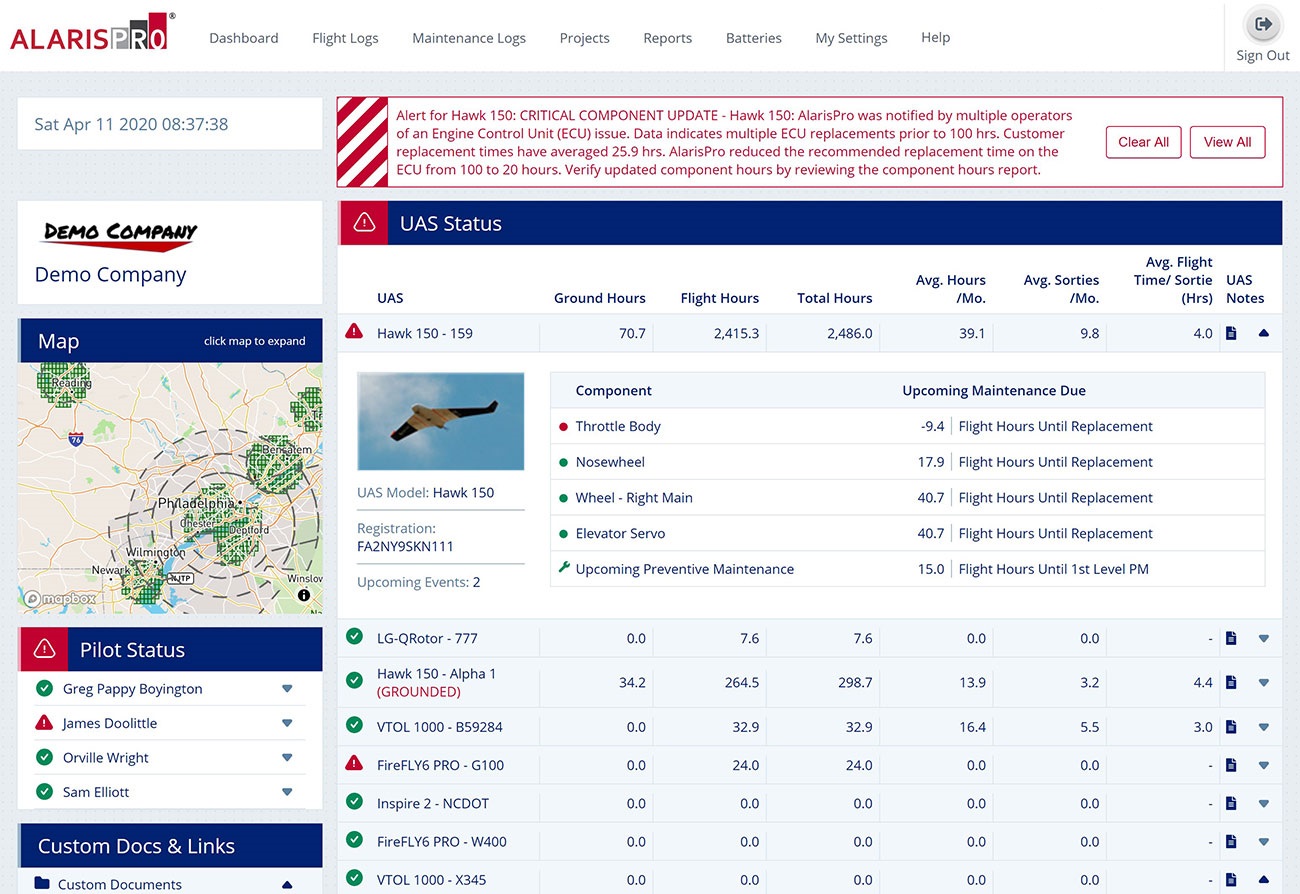

AlarisPro provides a centralized repository of everything related to your program. It’s a tool for understanding where the aircraft is in its lifecycle, where all the parts are in their individual life cycles as they support the overall aircraft operation, and the status of your crews and whether they are ready to fly. We organize this information through the use of status bars, reports, and automatic e-mails that we send to our customers. These reports say whether my fleet is ready to fly based on the systems of systems approach of all the components I mentioned. We provide a pilot status that checks whether your crews are “current”—another manned aviation metric. Do they have all the training requirements that are required internally as well as from a regulatory perspective, such as the FAA or another entity based on the country they’re flying in.

We also have an important feature that we call the alert status. Manned aviation utilizes airworthiness directives, customer bulletins, and other notifications to alert crews that there’s something that requires inspection, or a procedure has changed due to issues encountered. This type of alerting system is used heavily in manned aviation from the airline industry and all the way down to part 91 general aviation. We took that to a new level by providing near real time alerts to our customers to tell them, “look, there’s a software problem or there’s some other hardware issue.”

We’re very conservative in our component numbers. As we develop more data, we expand that conservative envelope to encompass more and more knowledge of the system and its components. We created a centralized repository to pull all that data together to intelligently answer the question: Am I ready to fly? Is the aircraft ready to fly?

The FAA is not going to change their approach to safety, nor should they change. Unmanned aircraft are still aircraft that fly over people and property. As organizations pursue expanded operations like beyond visual line of sight, flight over people, cargo operations, special government waivers and others, you need to be able to state that you can do it safely. To make decisions, the FAA relies on the same type of data that they expect to see for manned aviation. The unmanned industry needs to adjust to those standards. The FAA is not going to, they shouldn’t. It’s proven processes. And so, the industry has to adjust.

AlarisPro is a software product that’s based on those manned aviation standards and risk mitigation strategies. It’s a great way for organizations to prove the reliability and durability of their operation as they request approval for these expanded operations and also Type Certification and Production Certification for Manufacturers. The data needs to be presented in a format that the FAA is used to seeing. But we also have to remember there’s a business case for safety and reliability; as an operator or manufacturer, I need to be able to convince stakeholders that a $200,000 LIDAR isn’t going to fall from the sky. And so, it serves both a business and safety case.

We often talk about waiting for regulations to enable advanced operations and more complex missions that will truly enable the industry to scale, but can building the capability for managing these fleets and assessing and mitigating risk be an important step to enable regulations for these types of advanced operations? If so, how?

I think it’s a little bit of both, but I would err to the side that we need to provide a way to show that we can do this safely. I think that stems back to whether you are providing the data in a format that the FAA or other regulator is used to seeing. Obviously, if you were to consider an unmanned aircraft, the data requirements are going to be different than on a larger manned aircraft. And the FAA has done that, they scale back the data requirements correspondingly. But the format of that data still needs to be something they can use. It still needs to demonstrate that I’ve conducted flight operations reliably over a certain number of hours to make the case that I can continue to do it in a reliable fashion to where it will be safe, and I’m not putting the general public at risk, because that’s what the FAA is here to do. And so, I think it’s somewhat of a mix of the two, erring towards the industry needing to figure out a way to put this data in a format that the FAA finds acceptable.

In what industries are you seeing opportunities for enterprise fleets today? Where do you think this will grow in the future?

I think utilities is one that I see at the forefront right now. While there are requirements to crossover roads and, in some areas, people, a lot of the property that utilities cover is owned by the utility, so they can control their overflight of property and people in many cases. We have to do it safely. We can’t have aircraft falling into utility lines. Other examples are cargo delivery and engineering firms carrying expensive payloads. These two sectors share a common goal of carrying a critical and/or expensive payload safely and reliably. We have a lot of engineering firms that are doing LIDAR work with very expensive payloads costing up to two-hundred thousand dollars. Cargo operators carrying life-saving payloads also need to be able to show they can do this safely and reliably. All operators and manufacturers benefit from a dedicated fleet management program, but these are a few examples of early adopters.

If I were someone who was running a drone service company and I wanted to scale my operations, but the idea of fleet management seemed overwhelming, what advice would you give?

We’ve made it very simple for our clients without an aviation background to manage their fleet. We’re adding more flight log import features this fall but it only takes a few seconds to manually log a flight and our mobile app is even faster. If you have more than one flight, just push a button and tell us how much flight time you had, and it copies everything from the last flight. Our clients have commented to us that AlarisPro is very user friendly.

And when it comes to recording maintenance activities, each aircraft is already built up in the system so all you do is add a specific model to your fleet. We have all the components already in there. So, if you change a motor, you just have to tell us that you changed motor one, you don’t have to know what kind of part it is, AlarisPro already knows the component model or part number. It’s very simple.

It all comes back to when we first started this. We have a metric that we use on how long it should take somebody to log a flight. We’ve held to that. We always come back to it, and we’re always trying to reduce the amount of time that it takes somebody to record the data. We do have an importing function and some other features we’re working on that we’ll be releasing in the next few months. But for the most part, what we’ve done for the operator is we’ve made this as simple as possible. We want you to get lots of data out, and the goal was to make it as simple as possible for you to get the data in, so we can provide detailed reports with minimal effort.

What are some key takeaways you’d like our audience to know after reading this article?

One of the biggest takeaways is that there are two types of clients we focus on at AlarisPro—operators and manufacturers. What we offer is a two-way communication tool between participating manufacturers and our operator group.

We have manufacturers from around the world in our software, and when their customers use the software, our manufacturers can communicate notices and alerts to them down to the component level in real time. For example, they can communicate that they’re increasing or reducing the component replacement time for a specific component and provide a reason for the change. Or they can alert their customers to issues such as “Model X had a problem with a software load that had a bug in it so don’t fly until there is a patch.”

Also, as operators experience issues or problems with the aircraft or find themselves replacing components early—which is going to happen, you know, no aircraft is perfect—as a manufacturer, you want to learn these issues quickly, and you want to be able to see them catalogued and categorized into areas that can be made actionable.

For example, having a single motor fail at five hours on an aircraft where it was supposed to go a few hundred, that’s not necessarily an actionable piece of data. However, if you’ve got five or six motors failing at 5 hours, we’re able to notify the manufacturers so they can get on the problem right away to correct the issues.

It is important to note that operators and manufacturers are tightly connected through the aircraft and it’s supporting systems. And what we’re trying to do is increase the communication portal between those two groups to make the industry safer. That’s AlarisPro’s unique approach that I want people to walk away with.

Republished with the permission of Commerical UAV News.